ECHO: On “Gladiator” and “Muriel’s Wedding”

When Jamieson first asked if I might like to join this panel and discuss the topic of “Echo,” “In Authenticity,” the first thing that came to mind was Ridley Scott’s epic film from year 2000, “Gladiator,” starring Russell Crowe and Joaquin Phoenix. In an oft-quoted early scene from that movie, before his betrayal by the young emperor Commodus (Phoenix) and being sold into slavery, Maximus (Crowe), general of Rome’s northern armies, gives a pre-battle pep talk to his cavalry before they charge and decimate an opposing enemy horde of German barbarians. Maximus concludes his speech by saying, “Brothers, what we do in life, echoes in eternity,” reminding his troops that if they fight loyally and die in battle they will be glorified in death by finding themselves suddenly transported to an everlasting life in paradise.

This particular scene is memorable to me because I enjoyed the movie as a teenager when it was released as well as on every subsequent occasion for viewing again in adulthood. More likely however, I remember “Gladiator” so well because when it first appeared in theaters, the film was embraced with enthusiasm by American evangelical Christians as a kind of contemporary Hollywood prophecy and teaching tool in the various youth groups and sermons I attended as a pious young church-goer. As I understand it, the film was embraced in evangelical circles with similar zeal across the entire country. The family and friends with whom I grew up took this movie to heart in the style of histrionic moralizing that comes naturally to evangelicals, conferring upon the film the status of being holy-writ nearly to the point of addendum to biblical scripture, regardless of the fact that its most memorable quote about “echoes in eternity” is drawn directly from “Meditations” written by the decidedly anti-Christian second century Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius. No matter, late 20th century believers identified with its central conflict of human bondage versus eternal life. Ridley Scott’s moving images of never-ending war, circus entertainments and blood sport were not widely understood by evangelicals as forewarning the extravagant, incoming imperial violence of Bush-era adventurism, as perhaps they could have been, but taken for granted instead as metaphors for Christian brotherhood in the face of perceived daily persecution, of immortal souls enslaved as they struggle for spiritual freedom from various forces of cosmological evil. These self-described prayer warriors saw their own plight on earth reflected back at them, as well as the eternal reward in heaven due them for eschatological warfare conducted here and now in the present realm.

As fun as that film is to recall and reflect upon, I quickly moved on and tried to imagine another way of identifying the Echo phenomenon, perhaps as it might more closely resemble the original Greek mythology, or else relate to my work as an artist, and so immediately I thought of the Swedish band ABBA, and more specifically of P.J. Hogan’s 1994 cult film “Muriel’s Wedding” starring Toni Collette and Rachel Griffiths, for which ABBA famously provided several of their most popular songs to be included as soundtrack.

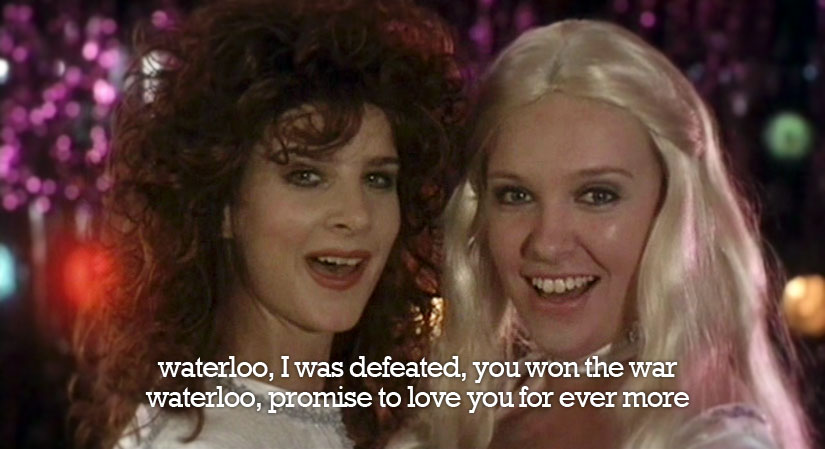

During one well-known scene, the two unpopular and slightly off-kilter main characters Muriel (Collette) and Rhonda (Griffiths) have just become best friends and now find themselves together onstage at a tropical island resort karaoke bar lip-synching ABBA’s international megahit “Waterloo” in full disco costume for a crowd of mean girls who hate them. The performance is the culmination of these two young women coming into the full potential of their friendship in spite of the bitchy, small town close-mindedness that dominated their worldviews just prior to taking the stage, the soon-to-be inseparable pair guided to this point in their lives not by faith in the afterlife but by the hyperbolic power of pop music.

According to synopses of the Greek myth, Echo was a beautiful nymph with a talent for singing. But after consorting with Zeus, Echo was cursed by Zeus’s jealous wife Hera, who made it so that Echo could only use her voice to repeat the most recent words spoken or sung unto her by another. Later on, when Echo finds and falls in love with the beautiful Narcissus after spying on him in some woods, dangerously close to a reflecting pool, Hera’s curse renders her unable to intelligibly communicate with the one great love of her life, and so following their inevitably trite miscommunication, she is doomed to watch him die in perverse confusion as he falls deeper and deeper in love with his own reflection.

Karaoke is the only form of public singing that I have engaged with since singing hymns and spiritual songs in the churches where I was raised. The two forms of public singing are vastly different, but perhaps they share some aspirational quality. The earlier hymnal experience is characterized by the communal and joyful, albeit totally sober, weekly worship of a benevolent, jealous, omnipresent father God. The other, occasionally ongoing experience is, for me at least, a much drunker, pagan elevation of the narcissistic self to ersatz pop star by way of echo, of mimicry, pantomime, the repeating of love song lyrics originally sung by another, much more famous and often godlike performer.

The last time I sang karaoke was several weeks ago at Swat Bar on Canal Street. I sang “Waterloo” by ABBA with Muriel and Rhonda in mind. ABBA’s use of Napoleon’s famous losing battle as a way to describe a surrender to love, to fate, or to destiny reminded me again of Maximus’s rousing speech to his Roman army. ABBA sings: “the history book on the shelf / is always repeating itself” and later, “Waterloo – I was defeated, you won the war / Waterloo – Promise to love you forever more…” negotiating romantic tropes is its own kind of battle, with its own style of eternity. Finally, it occurred to me that what ABBA did in life might actually echo for all eternity, always repeating itself on radios, on mp3s, on Broadway, in film soundtracks, in karaoke bars…

I sang very badly, but I always do. The point is not to perform well; the point is to do it as poorly as you do and to hear yourself singing, failing to live up to the aspiration of a fully embodied popular romance while repeating another lover’s lyrics, much as Echo would, and then in your own way die on the stage as Narcissus dies at the pool.

Now to pivot and pour all of these thoughts onto an interpretation of my recent work as a painter, much of which has been about copying photographic images and earlier art-historical paintings, colored or shaded with the various attitudes of popular culture. Celebrities or celebrated images populate my pictures frequently and promiscuously. Not unlike the amateurism of karaoke, I sometimes think of my paintings as a kind of fraud, or else, as being inauthentic revisions with spurious agendas that nevertheless seek to venerate grossly familiar imagery into something truly iconic. I source my work from the catalogue of pop phenomena that has existed as Google-able public record throughout my entire adult life. With regard to artistic forebears, I wish I could paint like the French hybrid post-Impressionist realist symbolist Henri Fantin-Latour but I cannot, so I just copy his paintings. With regard to torch singers, I wish I could sing like Mary J. Blige, but alas, I cannot, so I go to karaoke every once in a while. Some part of me wants to be something more excellent than what I am, so I take advantage, I copy, I repeat, I echo, and so on, entertainment everlasting.

This essay was presented at James Fuentes Gallery on April 12, 2017, as part of the seminar and panel discussion organized by Jamieson Webster and Vanessa Place, “ECHO; in Authenticity,” with Jack Halberstam, Evan Malater, and Naomi Toth.